“Burn This Up” - Beekeeper’s Letter from Africa, 1891

There’s not much left of Africa, Ohio. If you drive up Lewis Center Road you will see a church, a saloon, and a carry out. Also several historical markers, detailing Africa’s past. With a name like “Africa,” you cannot help but reason that this hamlet had connections with abolitionism, freedmen, or their aftermath. Oddly, perhaps, most of the African Americans who lived in Africa (Ohio) left for Westerville or Delaware after the Civil War. Is Africa even part of the history of Westerville?

I think it is part of our story. Africa was the next stop north of Westerville on the Underground Railroad, as we shall see. The town had other connections to Westerville. At one time, Africa had a fourth class post office.[1] The smallest class of office, most of its work consisted of forwarding mail to the Westerville post office. In 1891, one of these letters-in-transit told the story of an apiarist, or beekeeper who lived in Africa (Ohio). Like many nineteenth century letters, this one was full of spelling and grammatical mistakes. It tells, or hints, at some doings in the Africa area, so lets see what was the buzz in Africa.

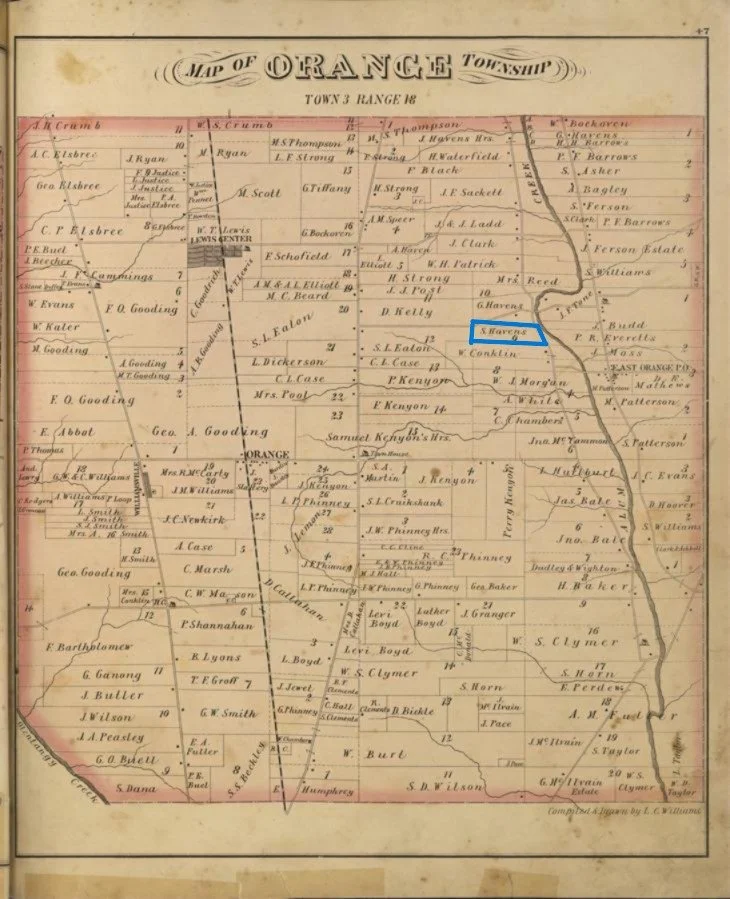

We don’t know who wrote the letter, except that they lived in or near Africa. The 1890 Census, which might have held fresh information, was destroyed in a fire in 1921. We have only the recipient's names, Blake and Clara Havens, in Dexter, Kansas. Blake and Clara may have been visiting, because they are listed in subsequent censuses in Orange Township, Delaware County. [2] Was the writer of our letter a friend or relative of Blake Havens? Maybe, but we would have to speculate more than I am comfortable doing.

A few quotations from the letter:

Ock came over monday and looked over the hives found one that was queenless tomorrow we are going to Del[aware] and if we can find Dr. Bessa get one of him

You don’t have to be a professional beekeeper to know that beehives have a female autocrat known as a “queen.” All of the hive’s other females are “workers,” and cannot reproduce. Male bees mate with the queen and then die, having fulfilled their usefulness. A hive which has no queen nor offspring descends into starvation, chaos, and disorder, until a new queen is introduced or raised internally. In this case, the correspondent had to travel to Delaware and get a queen. “Dr. Bessa” was likely R. Henry Besse, a Civil War surgeon, practitioner, and farmer, who won a prize at the 1886 Delaware County fair for his potatoes.[3]

Wm is gone down to draw your fathers bees over to Ocks he has rented them he gets Wm to draw them and he rides his grey mare; he went through the yard with quilts sheats and so on to tie around them he sold Aron for 65 dollars to the Livery man that bought Dr. Taylor out.

The family was serious enough about bees that they would travel some distance to expose their hives to pollen sources. We can assume that the quilts strapped around Aaron the horse were to prevent bee stings. Poor Aaron; who knows his final fate! It may have been worse than bee stings.

There is to be a Sunday School Picknick [sic] in Pattersons woods next Sat. but if it continues as cold as it is now it will have to be postponed I fear W will have a picknick with them bees to night

Sunday Schools were a major part of any congregation’s social and educational program. Picnics were often held after the worship service and formal teaching session, giving churchgoers of all ages to unwind. This picnic was held in the woods belonging to Samuel Patterson, one of the founders of Orange Township and active in the Underground Railroad. Runaway slaves stopping at Westerville’s Sharp House would then head north to Samuel Sharp’s house in Africa, possibly taking cover in his woods.[4]

Billy is doing the best he can, has the corn all cutt [sic]

If there was any doubt that the family were farmers, this short line should ease it. Billy, who was perhaps young, did what millions of young farm kids did in September and October, and cut corn. Corn was cut and dried in the field. A corn shock, still familiar to us as a Halloween decoration, was made by twisting four or more stalks together into a “gallus,” of square prop. Rooted in the ground, the gallus served as a prop for the cut stalks. Corn shocks became redundant after World War 2 with the introduction of the combine harvester.

I had the last of the sweet potatoes you gave me for breakfast this morning.

Sweet potatoes for breakfast? There may have been several reasons for this slightly odd menu choice. Keep in mind that reliable home refrigeration was still half a century away. It may have been a choice to eat them or lose them. Besides, honey is good on sweet potatoes, and the family, presumably, had plenty of honey.

Burn this up.

Delaware County produced 20,977 pounds of honey in 1889, and 126 pounds of beeswax.[5] That is an easily found statistic. Unknown is why our correspondent concluded by asking her recipients to destroy the letter. Families are often jealous of their privacy, but there may have been other reasons. Understandable, but how lucky for us, more than a century later, that it survived and we could share this glimpse of a vanished world.

Alan Borer

The Havens family owned land just north of "East Orange," the official name of Africa.

[1] https://postalmuseum.si.edu/closing-post-offices-%E2%80%93-the-first-time-around#:~:text=A%20fourth %2Dclass%20postmaster's%20position,in%20an%20article%20from%201901.&text=A%20Kentucky%20 newspaper%20editor%20was%20less%20understanding%20of%20their%20plight.&text=References:,)% 2C%20November%2028%2C%201901.

[2] https://www.familysearch.org/en/tree/person/details/LKKF-SZX

[3] Delaware Democratic Herald, September 23, 1886

[4] History of Delaware County and Ohio. Containing a brief history of the State of Ohio ... biographical sketches ... etc. Perrin, William Henry.

(Chicago, 1880), pp. 716-17.

[5] https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1890/volume-5/1890a_v5-10.pdf